| COMET Myopia Control Study ReconsideredA commentary on the COMET study testing the effect of progressive addition lenses (no-line bifocals) on the progression of myopia |

Many researchers believe that near work leads to nearsightedness, also called myopia. The “minus lens” which is usually prescribed to make distant objects clearer for nearsighted people, also increases the optical nearness of near work. Therefore some eye doctors have prescribed “plus lenses” for reading that put the eye in a “far seeing” position, mitigating the effect of near work, and have clamed success. Researchers and clinicians such as Martin Haberfeld in the 1930s and Kenneth Oakley and Francis Young in the 1970s found that the progression of myopia can be reliably stopped in those who use plus lenses for reading, whereas those who wear minus lenses continue to progress at the rate of about a half diopter per year.

The COMET study, whose results were published in 2003, was a randomized clinical trial designed to test the effectiveness of plus lenses against the progression of myopia in children. Progressive addition lenses (PALs), also called “no-line bifocals” were used in the experimental group. After three years, the study found practically no difference between the group that wore the PALs versus the ones that wore standard lenses for myopia.

It has been said that the COMET study proved that plus lenses do not inhibit myopia and that minus lenses do not exacerbate it. However it would be more correct to conclude, in light of the success of Haberfeld and Oakley/Young, that all it proved is that the COMET study PALs are a poor form for plus lenses. In other words, the “plus” part of the PAL was not used; the PALs were, in practice, the same as minus lenses. According to the study:

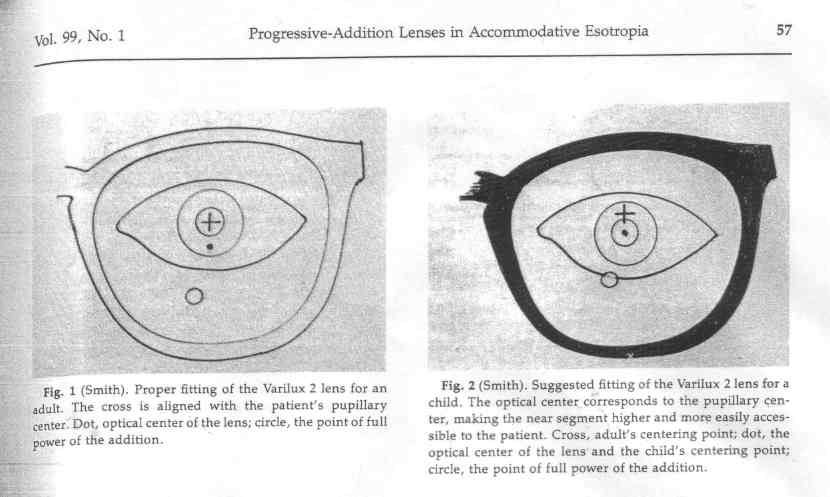

PALs were fitted with the top of the channel [sic], 4.0 mm above the pupil, allowing at least 11 mm for distance vision.* The fitting protocol was designed to encourage the children to use the near-addition portion of the lenses, because unlike adults with presbyopia, for whom the glasses are typically prescribed, children can accommodate and thus have no need for a near addition for close work.Let us look at the original figure from the article by Smith, which was actually published in 1985 (PubMed 3966519):* Smith, J. (1998)[sic] Progressive-addition lenses in the treatment of accommodative esotropia Am J Ophthalmol 99,56-62

So we see first of all, that the placement of the plus segment is crucial to the effectiveness of the plus lens. However, contrary to the description in the COMET report, according to the figure in the Smith article, the plus add does not come into play unless one looks down. Couple this with the fact that in progressive lenses, there is distortion (astigmatism) to the left and right of the plus zone (for details see figure 5 under Optical Properties of Progressive-Addition Lenses), children would be disinclined to use the plus add if it were possible to see clearly through the un-distorted upper portion. The children were “masked” and not told the purpose of the plus segment. In the report on adaptability we are told:

During the dispensing visit, the COMET optician verified the study fitting protocol measurements and proper frame adjustment, and assessed whether the child was using the lower portion of the lenses for reading materials. Regardless of lens assignment, the COMET optician instructed the child to use the top part of the glasses to focus on distant objects and to use the bottom part of the glasses for reading and near tasks. At every visit, the children were encouraged to follow the COMET wearing instructions protocol for using their glasses, which included suggestions for changes in head posture, eye, and/or head movements, if necessary, to see more clearly with their glasses.

So apparently, the children were told that they should use the bottom segment for reading only once, when they were first issued their glasses by the optician, and at most whenever a change in glasses was warranted, not more frequently than once every six months. Granted, we are told "With only a few exceptions, all of the children in the PAL group (99-100%) were observed to correctly use the lower portion of their lenses for reading, recorded at 6-month intervals." We are not told the nature of the assessment. According to Nakatsuka and colleagues at the Okayama University Medical School, the glasses commonly slip downward, making use of the upper portion more likely. It is significant that none of the survey questions had anything to do with how often the lower portion of the lens was used for near work. The emphasis was on obtaining “clear images,” and “comfort” — not using the reading addition for all near work. The actual instructions that the children took home with them were the following, from the same report:

The instructions to “lower the eyes to use the near addition while reading” are vague, especially if the design of the lens has not been revealed, as was the case in this “masked” study. The instructions should have said “look through the lower part of the for viewing near objects such as when reading, doing homework, or playing electronic games.” The instructions to “lower the eyes” could be interpreted to mean drooping the entire head, which could cause the eyes to point up and look through the top part of the lens. Also note the absence of any instructions to keep the frames from slipping down the nose. The emphasis is always on “clarity.”

- Tip chin down to view distant objects clearly if necessary.

- Lower the eyes to use the near addition while reading.

- If objects to the side do not appear clear, move head sideways until object clarity improves.

- If objects in front do not appear clear, move eyes or head up or down until object clarity improves.

- Return immediately for any frame adjustments.

- Do not adjust frames or reinsert lenses at home. All frame adjustments must be done by one of the research staff.

- Do not use super glue on any part of the frame or lens. If the frame breaks, return to the study center for an immediate replacement.

But clarity is not an issue for most young people with full accommodative range. They can easily use the full-minus top portion for all viewing, and that is exactly what the “control” counterparts were doing. Indeed, what the COMET study found is that only those children for whom reading through minus lenses caused the most discomfort and blur (those with lag of accommodation and nearpoint esophoria) received any benefit from using the PALs. This makes sense because these groups of children are precisely the ones with a natural incentive to use the PALs correctly.

So what the COMET study actually showed was not that plus lenses are ineffective in controlling myopia, but rather that PALs are ineffective in providing the plus power needed in order to counteract the effects of near work.

home page...

home page...